How a spirit born of the slums is overcoming decades of neglect

FOR six weeks in summer, the heights of an inner city park are a blaze of colour in a district more accustomed to being painted black.

This festival of flora, the blooms of up to 90 million wildflowers, peaks around the June solstice in a location celebrated for its views down on to the Liverpool waterfront and across to Cheshire, Wales, and the mountains of Snowdonia.

But this is also a burial ground. Beneath these slopes lie the memories of a proud community, and the remains of the hundred steeply terraced streets which housed them, wiped from the map in the name of urban renewal.

As the sixties started to swing, so did the wrecking ball that brought three decades of destruction to a famous working class district, many thousands of its inhabitants uprooted and shunted out to the far reaches of the city in the slum clearance scheme alone.

Those who stayed were herded into high rises on the false promise of better lives and then blamed when, in a few years, the towers became barely habitable. Twenty years after their construction, the worst of the blocks came down and many of their occupants, like their fathers before them, were moved away.

The slopes were returned to nature, a great park constructed. But after years of decline and depopulation, what had been one of the UK’s most thickly settled districts was by now struggling to provide its schools with students, its shops with customers. And many asked the same question: Who is this park for?

It’s the story of a community that decided it had taken enough...

This is a story about Everton. Not the football club, with its millionaire players and billionaire backer. This is the Everton near the top of every league table of economic and social deprivation. But that’s not where the real story lies.

That’s to be found beyond statistics about poverty and unemployment, in a place where the spirit born of the slums burns brightly still.

It’s an object lesson in what happens when you include a community in developments profoundly affecting their lives, and what happens when you don’t.

It’s the story of a community that decided it had taken enough. And some of the champions of that story. Like the man who talked a Tory minister into restarting a huge regeneration project, halted in its tracks by a new Conservative government.

And the twelve-year-old boy who stood in a crowd ringed by drug dealers and told them: “This is our community”.

Many times along the way, those in the vanguard have been told it can’t be done, that what they wish for is impossible; not only by those in authority, but from within their own ranks by those who had long learned to expect the worst.

The first time I visit West Everton Community Council, a young woman shows me the way. Smiling and confident, she tells me she went to the school next door, Faith Primary, where the world-renowned Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra teaches violin to five year olds.

How’s that going, I wonder. “Great”, she says. “The kids want to do everything now”.

Inside, WECC community development head Ann Roach’s involvement has been key to much that is positive in this neck of the woods. In between organising projects and activities, she sees first-hand the everyday struggles faced by many.

Roach began her campaigning half a century ago, aged nine – stamping hands for baked potatoes at a bonfire party for local children – later as a mother worried for her children, now a paid community worker, but ever mindful of what it's like to have nothing because "I was one of them".

It’s February when I first see her, and cold, adding to the challenge of a parent for whom school holidays are less about relaxing, more about coping.

“Families who haven’t got a loaf to put on the table”, says Roach. “Or they’ll go without themselves, or have coats on over the kids because, when it’s half term, no one gives them money to keep the heating on all the time".

“Behind the door”, adds local Labour councillor Jane Corbett, “the level of poverty is now extreme”. She and Roach are old friends, fellow campaigners, sisters in arms since the early eighties.

We used to take turns cleaning the blocks, but this one we left for Maxy to see how it really was. When he came out he spewed all over his lovely shiny shoes

“You see them melting because they’re losing faith in themselves as parents", Roach adds, “and all that becomes anxiety, depression and no hope for some of them.

"And they’re not all on benefits", she adds, suddenly angry. "We have to wipe this benefit thing out”.

She recounts a visit to a branch of a certain high end, high street department store, telling me, almost apologetically, that “I’m lucky enough to be able to shop there, because I am in work, and it was only for three things for my granddaughter”.

There, she overheard an assistant holding court among colleagues. "He said, 'You know, I just think it’s these estates with non-educated people on benefits'. My blood was boiling”, says Roach.

“I tapped him on the shoulder and said ‘Excuse me, I’m one of those non-educated people, I’m coming here to keep you in a living. You go out that door, you see that Matalan there, he (owner John Hargreaves) is off the same estate as me. Don’t you ever judge anyone'.

“People don’t know how hard it is for some of them to get out that front door, or go the doctor’s, they’ll take the kids but they won’t look after themselves.

“One of the things about being in poverty is if you have to go for a breast scan, it’s at Broadgreen or Fazakerley (hospitals) and it’s £5 on the bus, more if they’ve got the kids with them, so they could be dying because they can’t afford to go for that scan”.

On the other side of the park, Bob Blanchard was among a nucleus of disaffected residents who, after years of “deprivation, poor housing, poor health, high crime, high unemployment, poor educational attainment, decided we wanted to create change for the better”.

The upshot was Breckfield and North Everton Neighbourhood Council and, with £750,000 of Big Lottery money and match funding from Europe, a purpose-made community centre training young adults (as business administrators, community workers and more); supporting a grow-your-own programme for those without gardens (five greenhouses and abundant vegetables and fruit trees means “everyone does a bit and everyone gets a bit back, it’s going back to socialism”); a nature trail (“a lot of the kids have never seen a carrot in the ground”), health programmes and 10 computers for public use.

“Everton has one of the lowest computer ownerships in the country", says BNENC development chief Blanchard. "Job search, banking, property pools for housing, everything you do now is online. If you’re unemployed and on benefits, how can you afford £20 to £25 a month for your internet?

“A lot don’t know how to use a computer, so we set up an email account, open their DWP account for them, give them one-to-one support so they don’t get sanctioned”.

We meet at Liverpool Veterans HQ on Breck Road, where Blanchard is chairman, and eight years ago was the driving force behind the first one-stop centre for former Forces personnel in England and Wales.

“Did you come on the bus?”, I’m asked – a reasonable assumption in a district which also has one of the lowest car ownership rates in the country.

Blanchard insists: “If you dwell on negativity you’ll never progress. When New Labour was ousted by the Conservatives, the regeneration programme in this area stopped overnight, half way through a major house-building programme.

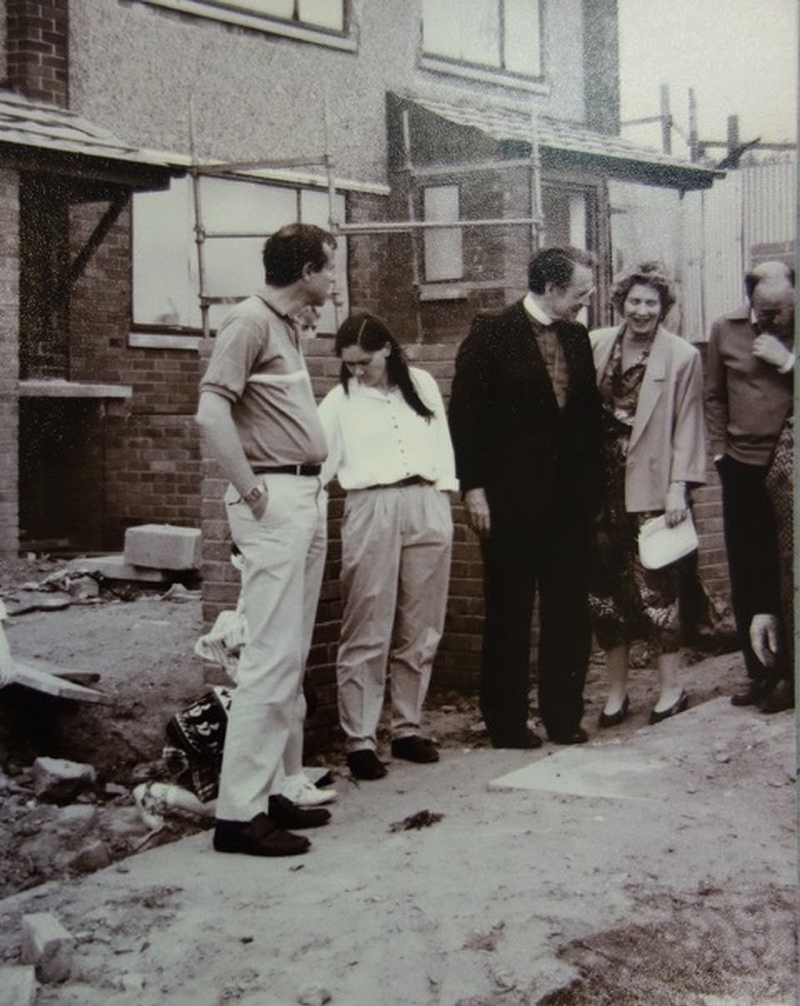

“We put reports together, sent them off, and then (Housing and Communities Minister Eric) Pickles came up and we took him round and said this is what we’ve done so far, showed him all the good, then we showed the boarded-up buildings, and said ‘This is what your government has left us with’.

“Within two months we’d got funding to restart the programme. So communities can sway governments but it’s got to be done in a positive way”.

In Everton, politics hovers over every conversation. Roach’s antipathy towards the country’s rulers is about more than tribalism: only in places like Everton can you truly appreciate the degree of damage inflicted, intentionally or not, by ten years of austerity.

“It’s all right the government saying, ‘these lazy gang of bastards,'” she says. “Well, sorry, what did you ever do to help these kids? All this government is doing now is a slow death to all of us”.

Yet it was a Labour administration that would provoke the fight of Everton’s life. Not any old Labour administration, mind.

The light that lit...

The eighties were a defining time for Everton. The mistakes of the sixties were to be repeated as failure to properly consult residents over a new wave of demolition brought fresh misery for many. Only this time, the decision-makers would push it too far.

A rent strike by occupiers of Crosbie, Canterbury and Haigh Heights in the early seventies had brought little reward. Their protest was over conditions in the three tower blocks, so grim that locals darkly dubbed them The Piggeries. But, according to one account of the time, many council employees blamed tenants for their plight and requests for repairs were, literally, binned.

As the high rises were razed, the Radcliffe Estate, its design based on an idyllic Cornish village, was intended to provide a fresh start for some. What might have worked for a quiet seaside community proved disastrous for Everton.

Rows of houses were separated by narrow corridors on one side, alleyways the other. For drug dealers its layout was a dream and by the early eighties they controlled it.

When a young woman, selling sex to fund addiction, was found dead, a meeting of residents was called. Corbett, back then another concerned mother and local campaigner, recalls: “It was standing room only. The dealers were at the back, watching everything, you had to be very careful.

“Then one of the kids stood up at the front. He was about twelve and he said ‘I want to say something’, and people said ‘Go on lad’. And he said ‘This isn’t right, this is bad what’s happening here, we need to sort this out, we’re a community’. And everybody cheered”.

Roach says: “That was the start of the Radcliffe Action Group. People were scared, but they also wanted something for the kids because there was nothing, so we organised days out and parties.

“It wasn’t a cover because it was needed but it was a way for people to come to the play scheme and tell you about the drugs, but without being watched”.

After Radcliffe, the community was more organised and would need all the support it could rally as, early in 1984, a militant-influenced Liverpool City Council announced a regeneration project for Everton.

A grand Victorian-style park was planned, necessitating the demolition of an entire estate. The community welcomed the park scheme but fiercely opposed losing what they saw as perfectly good four-bedroom family houses on three streets, plus a thriving youth centre.

In October 1986, five four-bed houses at the bottom of Arkwright Street were bulldozed. In his account of the time, Rev Henry Corbett, husband of Jane and vicar of St Peter’s Church, writes: “What were we to do? Stand idly by?”

Five days before Christmas, the last resident moved out of the next homes on the wrecking crew's list, handed her key to the newly-formed Langrove Street Action Group, and the 'Langrove Squat' began, forcing a halt to the demolition.

A rota of squatters – mothers, churchgoers, clergymen from both sides of the Christian divide, the Corbetts, Ann Roach and others – occupied the house throughout Christmas and the New Year, supported by the city's Catholic and Anglican leaders, Archbishop Derek Worlock and Bishop David Sheppard.

The fight went to court, but outside the circle of occupiers there was little optimism. One squatter, Billy Howarth, would be told repeatedly over a pint in his local that they had no chance.

Days before the end of the case, 47 Labour councillors were surcharged and disqualified for failing to set a budget rate for the city on time. A newly elected Labour administration backed the campaigners, the Langrove Community Housing Co-op Ltd was registered and, in June 1990, Oscar-winning actor and political activist Glenda Jackson officially opened refurbished homes in Langrove Street, Rose Vale and Arkwright Street, telling campaigners: "You are living proof it is people that matter and not things”.

It’s about their confidence because we tell them they are all beautiful, the girls and the boys

What happened next may just be unique in the history of urban redevelopment, a case study in community inclusion, requiring the planets to align and bring together all the people in all the key positions, all wanting the same outcome.

Corbett says: “Langrove was what we call the light that lit, because when we won that we thought, ’we can do this again!’”

This time campaigners turned their attention to a one-and-a-half mile stretch from Prince Edwin Street - south into the city centre - areas of which were virtual no-go zones, where bin lorries would not enter without protection.

A council starved of resources had stopped repairing the maisonettes, fertile ground for the drug dealers. Roach recalls: “We had to escort the binmen, they were petrified of needles, glue, people asleep in doorways. People were scared to fight back, they’d been threatened with shotguns.

“We decided no one’s going to do anything so we’re just going to have to do it ourselves. Again”.

The Islington Action Group was formed to drive forward their hopes. Max Steinberg (now head of Liverpool Vision but then with the former Housing Corporation) came to see the state of the maisonettes for himself.

The blocks had nicknames, mostly ironic. The VIP block, the worst of the worst, was “full of shit. It stunk. We used to take turns cleaning the blocks, but this one we left for Maxy to see how it really was. When he came out he spewed up all over his lovely shiny shoes”.

Others came on board: Catherine Meredith, an architect “really positive about communities having their say” and Paul Edwards, a council community development officer, who Roach met by chance at a kids’ disco and went on to train the residents as experts in regeneration: “Who we go to, where we get money from, how we get it”.

Corbett says: “It was the first and the last time that people who understood and supported community development all came together – good people at the council, private investors, Max, CDS housing, Wimpey, all linked with the government and all controlled by a strong community”.

The maisonettes came down and their replacements, built off the existing foundations, designed by residents, using beermats and cornflake boxes. “We interviewed and chose the planners and the developers. We decided what wood we wanted on our doors, bathroom suites one night, tiles another day”.

Housing Minister Sir George Young was to launch the development in London but Roach was having none of it. “We said how can you launch it in sodding London, you haven’t even seen it, so come and launch it here please”.

And so a helicopter carried the Conservative Secretary of State from the capital to a field in Everton and he performed his official duty standing in the former Crescent pub, behind a pulpit borrowed from the local church.

The road back

Everton is rich in heritage, among it: St George’s aka the Iron Church, one of the world’s first buildings with a cast iron frame and the inspiration for New York’s skyscrapers; the stunning Grade II listed library whose first users, in 1886, knew it as the 'jewel on the hill'; the 18th century lock up 'for unruly revellers', now part of a park history trail; and the famous centrepiece of Everton FC’s crest.

None of these treasures could mask the destruction wrought by years of neglect and calamitous decision-making by those in authority. For all the euphoria of the Islington Action Group’s achievements in the nineties, by then the population was devastated, infrastructure collapsing, schools, health centres and churches threatened with closure.

As pupil numbers declined, seven schools were earmarked for demolition. Roach says church authorities believed a divide-and-conquer strategy would see through the closures.

“They thought we’d fight for our own individual schools but we rang round all the parents and called a meeting and we agreed we’d stick together.

“A Catholic brother said to me, ‘you should be ashamed. What are you doing fighting for all these schools when it’s our school you should be fighting for?’ And I said ‘you’re supposed to be a man of God, fighting for every child.’”

He told her it was a lost cause. Two years later, four of the schools – Holy Cross, Trinity, St John’s and Friary – were saved. Friary became Faith, an ecumenical school, another bridge across the narrowing religious divide.

In Everton now, educational standards steadily improve. When the North Liverpool Academy opened in 2006, one pupil went on to university. “Last year”, says Blanchard, school vice chair, “we sent 78 to study engineering, the sciences, law.

“We’re changing the outlook of young people because back then they wanted to be footballers. Some young girls wanted to be WAGs”.

At Faith Primary, playtime means picking up a cello alongside a member of the RLPO. Roach remembers fondly the start of a beautiful relationship, the In Harmony project, which has famously achieved dramatic increases in the health and academic attainment of pupils.

“People were going to sleep in bins outside the gates, and then this young man came bouncing in and said, ‘I’m Peter Garden (the Phil’s director of learning), what can I do?’ My eyes lit up and I said ‘please, yeah, please, please, please, please'".

Sceptics doubted the merits of pairing primary school children from one of the UK’s most deprived districts with an internationally celebrated orchestra. “They said it wouldn’t work putting it in a poor area, but honest to God the pride that comes from it makes me cry.

“Every child in the school, and the teachers, the cleaners, the lollipop man, get taught on the same level, and no one is the better class or the worse class”.

Among the members of West Everton Children's Orchestra on stage for In Harmony’s ninth birthday concert at the Philharmonic Hall, in March, were many from black and minority ethnic backgrounds. It’s a reflection of the changing demographic as the population grows again, and unimaginable even at the start of the millennium when TV news cameras were pointed at Everton, showing asylum seekers, billeted to the towers, abused and assaulted.

Young people want to come back – they've tried it elsewhere and don’t know their neighbours

Seventeen years on, Corbett adds perspective to that media horror show. She says many in the community provided whatever support they could to hundreds of refugees crammed by the government into homes unfit for human habitation.

Isolated problems still occur. One family from eastern Europe were, Roach says, “vulnerable' - they got passed on and passed on, they caused disruption and it all went terribly wrong”.

“But another family, from the Middle East, were completely on their own and local families looked after them, got to know them, and they’re the stories you don’t hear”.

Roach argues that what can appear to be racism often has nothing to do with people’s origins. “It’s people being on housing lists, waiting for a property to come up, then they see a family who they don’t know, from another country. It’s not being wicked, it’s just saying ‘why didn’t we get that?’ It’s not about racism, it’s about being on a waiting list.

“It’s been predominantly white working class people in these areas and now we’re getting people from all over, which is making it an even more special community”.

Elsewhere, the Grand Secretary of the Grand Orange Lodge of England still has his office in Everton but a once notoriously bitter divide between the district’s Catholics and Protestants is largely gone.

Rather than fighting one another, says Rev Corbett, “people decided it was better to be fighting for the real things in life, like good homes and safety”.

The here and now

At Shrewsbury House Youth and Community Centre – The Shewsy – team leader John Dumbell carries on the work of dismantling barriers, removing "misunderstanding and ignorance", into a new generation, with football matches between mixed teams of white and black teenagers and trips introducing Shewsy members to other cultures and religions. “They see that no matter where in the world, kids always have similar interests”.

Only good news is shared by youngsters taking part in the nightly Circle Time. "It's about giving young people a voice so they can make their own decisions”.

After-school provision in Liverpool averages £8 per child, says Dumbell. “In an area impoverished in so many ways, if you’re a working parent and on a low income you’re not going to be able to near afford that.

“So we pick them up from school and give them a hot meal for £1 per night. Very often they haven’t got a pound and we’re not going to turn them away”.

Healthy eating and exercise programmes build self-esteem. “Girls become more confident in the way they look, not that they think they are beautiful, or they’re not beautiful, it’s just about their confidence because we tell them they are all beautiful, the girls and the boys”.

So what of the future? Walk down Breck Road and you won’t strain to find faces, gaunt and careworn, that speak of long-term austerity. Don’t tell them the economy is strong.

Options for a night out in Everton are still severely limited, there are new fights to be fought – blocks of rented flats are being thrown up at an alarming rate, aimed at stag weekenders and students, which, Corbett says, are private investment boxes.

Plans to expand the scope of the 180-year-old Great Homer Street market – on a new site since 2014 – have stumbled. “Greatie market kept that area alive for years and that’s why it’s important we get that right”, says Corbett.

The new Great Homer Street development with Sainsbury’s at its centre is not perfect; with concerns that shop units going to, among others, a bookmaker and a fast food chain, bring more negatives than positives.

It is progress nonetheless, after a decades-long battle to convince one of the supermarket giants that there was the population to support it.

In all places where opportunities are limited, the drug dealer maintains a grubby allure, as Dumbell acknowledges. “It’s so easy to be influenced.

“With some,” he says, “you think they’ll never do that, they’re going great. And then they come and ask for a reference and you say, ‘Yeah, are you going for a job?' And they say, ‘No I’m going to court’ and I think ‘ah, f…'

“But with others you think, ‘they’ve got no chance, we’re not getting through to them’. And you’ll see them years after and they’ll say: ‘I never forgot what you said to me’. And they haven’t followed the path of their brothers or uncles and they’re in employment or college”.

Providing positive alternatives is a priority. One such came with two rat-riddled blocks on Soho Street. Corbett says: “They were going to pull them down, so we worked with LMH and said do them up as one-bed flats, make them energy efficient so they are cheap to run, with the majority for people with a local connection.

“It gives people a flat they can afford and a way of saying back to the drug dealers, ‘Go away, I’m sorted, I’ve got my own place and you’re still living with your mother’”.

Look around now, and housing provision has vastly improved. At the back of the Shewsy, and over by the water tower, that 19th Century triumph of engineering and architecture, stand hundreds of solid, attractive homes anyone could be proud of.

Preparing for Friday night's adult bingo session ("it can get a bit raucous") at West Everton Community Centre, Roach says a sense of togetherness persists in the area. “I think we’re one of the lucky ones, who’ve still got that spirit. Young people want to come back because they’ve tried it elsewhere and they don’t know their next door neighbours. As soon as the door shuts that’s it.

“People still feel like they belong in this community. If anything happens everyone’s there for one another, whether it’s a bowl of scouse or a bag of sugar or sorrys or happy birthday”.

Back on the high ground, the Friends of Everton Park invite former residents of those slopes back from Speke, Norris Green, Kirkby, to play a game of nostalgia involving a map of the park overlaid with a map of their old terraced streets.

When the park was created, says Ken Rogers 'Friend' - former resident, journalist and author of The Lost Tribe of Everton & Scottie Road - it may have felt “a threatening, lonely place”. Modern Everton Park is very different, first in the country to be awarded Grow Wild England flagship status, with future hopes for a bistro and visitor centre.

The Premier League football club, which took its name in the back room of an Everton pub 139 years ago, is keen to cement its spiritual links: a planned community event at the park will highlight those bonds and provide coaching for local youngsters.

“The Friends of Everton Park is about more than just the park, it is a movement, pulling the threads of the community together and taking it forward", says Rogers

"Great Homer Street was once Liverpool’s undisputed golden shopping mile, with a world-famous market, cinema and two department stores. You can’t lose all that, build high-rise hell, knock it down again, then build a park and expect to have utopia. It takes hard work.

“To have come as far as we have, we should be proud. We’re half way up the mountain”.